George Washington

| George Washington | |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office April 30, 1789 – March 4, 1797 |

|

| Vice President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Cyrus Griffin (as head of state) |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

|

|

|

| In office June 15, 1775 – December 23, 1783 |

|

| Appointed by | Continental Congress |

| Succeeded by | Henry Knoxb |

|

6th United States Army Senior Officer

|

|

| In office July 13, 1798 – December 14, 1799 |

|

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | James Wilkinson |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Hamilton |

|

|

|

| Born | February 22, 1732 Westmoreland County, Colony of Virginia, British America |

| Died | December 14, 1799 (aged 67) Mount Vernon, Virginia, United States |

| Resting place | Washington family vault, Mount Vernon, Virginia, United States |

| Nationality | American British subject (prior to 1776) |

| Political party | None |

| Spouse(s) | Martha Dandridge Custis Washington |

| Children | John Parke Custis (stepson) Martha Parke Custis (stepdaughter) Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis (step-granddaughter, raised by Washington) George Washington Parke Custis (step-grandson, raised by Washington) |

| Occupation | Farmer (Planter) Soldier (Officer) |

| Religion | Church of England / Episcopal |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1752–1758 1775–1783 1798–1799 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General General of the Armies of the United States (posthumously in 1976) |

| Commands | British Army's Virginia Regiment Continental Army United States Army |

| Battles/wars | French and Indian War

|

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal, Thanks of Congress |

| a See President of the United States, in Congress Assembled. b General Knox served as the Senior Officer of the United States Army. |

|

George Washington (February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731]– December 14, 1799)[1][2][3] led America's Continental Army to victory over Britain in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and later became the first President of the United States from 1789 to 1797.[4][5][6] His role in the revolution and subsequent independence and formation of the United States was significant, and he is seen by Americans as the "Father of Our Country".[5][6]

Born into a wealthy family in Westmoreland County, Virginia, Washington embarked upon a career as a tobacco farmer and plantation owner. In 1749 he was appointed to his first public office, surveyor of newly created Culpeper County, and through his half-brother Lawrence Washington he became interested in the Ohio Company, which had as its object the exploitation of Western lands. After Lawrence's death (1752), Washington inherited part of his estate and took over some of Lawrence's duties as adjutant of the colony. Washington gained command experience during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). Due to this experience, his military bearing, leadership of the Patriot cause in Virginia, and his political base in the largest colony, the Second Continental Congress chose him in 1775 as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.[7]

He forced the British out of Boston in 1776, but was defeated and nearly captured later that year when he lost New York City. By crossing the Delaware River in the dead of winter he defeated the British, taking them by surprise, in Trenton, New Jersey. Because of his strategy, Revolutionary forces captured the two main British combat armies at Saratoga and Yorktown. Negotiating with Congress, the colonial states, and French allies, he held together a tenuous army and a fragile nation amid the threats of disintegration and failure. Following the end of the war in 1783, rather than holding onto power, Washington resigned, returning to his plantation at Mount Vernon; prompting George III to call him "the greatest character of the age".[8]

Washington presided over the Philadelphia Convention that drafted the United States Constitution in 1787 because of general dissatisfaction with the Articles of Confederation. Washington became President of the United States in 1789 and established many of the customs and usages of the new government's executive department. He sought to create a nation capable of sustaining peace with their neighboring countries. His unilateral Proclamation of Neutrality of 1793 provided a basis for avoiding any involvement in foreign conflicts. He supported plans to build a strong central government by paying off the national debt, implementing an effective tax system, and creating a national bank. Washington avoided war and maintained a decade of peace with Britain upon signing the Jay Treaty in 1795, despite intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although never officially joining the Federalist Party, he supported its programs. Washington's farewell address was a primer on republican virtue and a stern warning against partisanship, sectionalism, and involvement in foreign wars. He was awarded the first Congressional Gold Medal with the Thanks of Congress in 1776.[9]

Washington died in 1799 mainly due to treatment for his pnuemonia, which included calomel and bloodletting, resulting in a combination of shock from the loss of five pints of blood, as well as asphyxia and dehydration. Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, delivering the funeral oration, declared Washington "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen".[10] Historical scholars consistently rank him as one of the greatest U.S. presidents.

Contents |

Early life (1732–1753)

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731][1][2][3] the first child of Augustine Washington and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington, on their Pope's Creek Estate near present-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia. According to the Julian calendar, Washington was born on February 11, 1731 (O.S.);[1][2][3] according to the Gregorian calendar, which was adopted in Britain and its colonies during Washington's lifetime, he was born on February 22, 1732. Washington's Birthday (celebrated on Presidents' Day), is a federal holiday in the United States. He was born at Pope's Creek Plantation, on the Potomac River southeast of modern-day Colonial Beach in Westmoreland County, Virginia. Washington's ancestors were from Sulgrave, England; his great-grandfather, John Washington, immigrated to Virginia in 1657. George's father, Augustine Washington (1694–1743), was a slave-owning planter who later tried his hand in iron-mining ventures. His mother, Mary Ball Washington (1708–1789), lived to see her son become famous, though she had a strained relationship with him. In George's youth, the Washingtons were moderately prosperous members of the Virginia gentry, of "middling rank" rather than one of the leading families.[11]

Washington, the first-born child from his father's second marriage, had two older siblings and five younger siblings.[12] George's father died when George was eleven years old, after which George's half-brother, Lawrence Washington, became a surrogate father and role model. William Fairfax, Lawrence's father-in-law and cousin of Virginia's largest landowner, Thomas, Lord Fairfax, was also a formative influence. Washington spent much of his boyhood at Ferry Farm in Stafford County near Fredericksburg. Lawrence Washington inherited another family property from his father, which he later named Mount Vernon. George inherited Ferry Farm upon his father's death, and eventually acquired Mount Vernon after Lawrence's death.

The death of his father prevented Washington from receiving an education in England as his older brothers had done. His education comprised seven or eight years, mostly in the form of tutoring by his father and Lawrence, and training in surveying.[13] Late in life, Washington was somewhat self-conscious that he was less learned than some of his contemporaries. Thanks to his Fairfax connections, at seventeen he was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County in 1749, a well-paid position which allowed him to purchase land in the Shenandoah Valley, the first of his many land acquisitions in western Virginia. Thanks to Lawrence's involvement in the Ohio Company, Washington came to the notice of the lieutenant governor of Virginia, Robert Dinwiddie. Washington was hard to miss: at about six feet two inches (estimates of his height have varied), he towered over most of his contemporaries.

In 1751, Washington traveled to Barbados with Lawrence, who was suffering from tuberculosis, with the hope that the climate would be beneficial to Lawrence's health. Washington contracted smallpox during the trip, which left his face slightly scarred, but gave him immunity to the dreaded disease in the future. Lawrence's health did not improve: he returned to Mount Vernon, where he died in 1752. Lawrence's position as Adjutant General of Virginia (a militia leadership role) was divided into four offices after his death. Washington was appointed by Governor Dinwiddie as one of the four district adjutants, with the rank of major in the Virginia militia. Washington also joined the Freemasons in Fredericksburg at this time.

Stories about Washington's childhood include the myth that Washington chopped down, or barked, his father's cherry tree, without permission, and admitted the deed when questioned, saying "I cannot tell a lie." Historians believe this tale was invented by Parson Weems after Washington's death.

French and Indian War (Seven Years War) (1754–1758)

In 1754, Dinwiddie commissioned Washington a Lieutenant Colonel and ordered him to lead an expedition to Fort Duquesne to drive out the French Canadians.[14] With his American Indian allies led by Tanacharison, Washington and his troops ambushed a French Canadian scouting party of some 30 men, led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville.[15] This action is regarded as the first hostility leading to the global Seven Years' War, as the French responded by attacking Fort Necessity which Washington had erected, and the British would later send two regiments to engage with the French.[16] Washington surrendered to the French Canadians and was released on parole, returning with his troops to Virginia, where he was cleared of blame for the defeat, but resigned because he did not like the new arrangement of the Virginia Militia.[17]

In 1755, Washington was an aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Monongahela expedition.[14] This was a major effort to retake the Ohio Country. While Braddock was killed and the expedition ended in disaster, Washington distinguished himself as the Hero of the Monongahela.[18] While Washington's role during the battle has been debated, biographer Joseph Ellis asserts that Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnant of the British and Virginian forces to a retreat.[19] Subsequent to this action, Washington was given a difficult frontier command in the Virginia mountains, and was rewarded by being promoted to colonel and named commander of all Virginia forces.[14]

In 1758, Washington participated as a Brigadier General in the Forbes expedition that prompted French evacuation of Fort Duquesne, and British establishment of Pittsburgh.[14] Later that year, Washington resigned from active military service and spent the next sixteen years as a Virginia planter and politician.[20]

Between the wars: Mount Vernon (1759–1774)

On January 6, 1759, Washington married the widow Martha Dandridge Custis. Surviving letters suggest that he may have been in love at the time with Sally Fairfax, the wife of a friend. Some historians believe George and Martha were distantly related.

Nevertheless, George and Martha made a good marriage, and together raised her two children from her previous marriage, John Parke Custis and Martha Parke Custis, affectionately called "Jackie" and "Patsy" by the family. Later the Washingtons raised two of Mrs. Washington's grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. George and Martha never had any children together — his earlier bout with smallpox at the age of 19[21] (possibly followed by tuberculosis) may have made him sterile. The newly wed couple moved to Mount Vernon, near Alexandria, where he took up the life of a planter and political figure.

Washington's marriage to Martha, a wealthy widow, greatly increased his property holdings and social standing. He acquired one-third of the 18,000 acre (73 km²) Custis estate upon his marriage, and managed the remainder on behalf of Martha's children. He frequently bought additional land in his own name. In addition, he was granted land in what is now West Virginia as a bounty for his service in the French and Indian War. By 1775, Washington had doubled the size of Mount Vernon to 6,500 acres (26 km2), and had increased the slave population there to more than 100 persons. As a respected military hero and large landowner, he held local office and was elected to the Virginia provincial legislature, the House of Burgesses, beginning in 1758.[22]

Washington lived an aristocratic lifestyle—fox hunting was a favorite leisure activity. Like most Virginia planters, he imported luxuries and other goods from England and paid for them by exporting his tobacco crop. Extravagant spending and the unpredictability of the tobacco market meant that many Virginia planters of Washington's day were losing money. (Thomas Jefferson, for example, would die deeply in debt.)

Washington began to pull himself out of debt by diversification. By 1766, he had switched Mount Vernon's primary cash crop from tobacco to wheat, a crop that could be sold in America, and diversified operations to include flour milling, fishing, horse breeding, spinning, and weaving. Patsy Custis's death in 1773 from epilepsy enabled Washington to pay off his British creditors, since half of her inheritance passed to him.[23]

During these years, Washington concentrated on his business activities and remained somewhat aloof from politics. Although he expressed opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act, the first direct tax on the colonies, he did not take a leading role in the growing colonial resistance until after protests of the Townshend Acts (enacted in 1767) had become widespread. In May 1769, Washington introduced a proposal drafted by his friend George Mason, which called for Virginia to boycott English goods until the Acts were repealed. Parliament repealed the Townshend Acts in 1770, and, for Washington at least, the crisis had passed. However, Washington regarded the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774 as "an Invasion of our Rights and Privileges". In July 1774, he chaired the meeting at which the "Fairfax Resolves" were adopted, which called for, among other things, the convening of a Continental Congress. In August, Washington attended the First Virginia Convention, where he was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress.[24]

American Revolution (1775–1787)

After fighting broke out in April 1775, Washington appeared at the Second Continental Congress in military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. Washington had the prestige, military experience, charisma and military bearing of any good military leader and was known for his reputation as a strong patriot, and the Southern States, especially Virginia, supported him. Although he did not explicitly seek the office of commander and even claimed that he was not equal to it, there was no serious competition. Congress created the Continental Army on June 14, 1775. Nominated by John Adams of Massachusetts, Washington was then appointed Major General and elected by Congress to be Commander-in-chief.[14]

Washington assumed command of the Continental Army in the field at Cambridge, Massachusetts in July 1775,[14] during the ongoing siege of Boston. Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. American troops raided British arsenals, including some in the Caribbean, and some manufacturing was attempted. They obtained a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) by the end of 1776, mostly from France.[25] Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston and Washington moved his army to New York City.

Although negative toward the patriots in the Continental Congress, British newspapers routinely praised Washington's personal character and qualities as a military commander. These articles were bold, as Washington was enemy general who commanded an army in a cause that many Britons believed would ruin the empire.[26] Washington's refusal to become involved in politics buttressed his reputation as a man fully committed to the military mission at hand and above the factional fray.

In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a massive naval and land campaign designed to seize New York and offer a negotiated settlement. The Continental Army under Washington engaged the enemy for the first time as an army of the newly declared independent United States at the Battle of Long Island, the largest battle of the entire war. Some historians see his army's subsequent nighttime retreat across the East River, without the loss of a single life or materiel, as one of Washington's greatest military feats.[27] This and several other British victories sent Washington scrambling out of New York and across New Jersey, which left the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up his victory at Trenton with another at Princeton in early January. These victories alone were not enough to ensure ultimate victory, however, as many soldiers did not reenlist or deserted during the harsh winter. Washington reorganized the army with increased rewards for staying and punishment for desertion, which raised troop numbers effectively for subsequent battles.[28]

British forces defeated Washington's troops in the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. Howe outmaneuvered Washington and marched into Philadelphia unopposed on September 26. Washington's army unsuccessfully attacked the British garrison at Germantown in early October. Meanwhile, General John Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army at Saratoga, New York. France responded to Burgoyne's defeat by entering the war, openly allying with America and turning the Revolutionary War into a major worldwide war. Washington's loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing Washington from command. This attempt failed after Washington's supporters rallied behind him.[29]

Washington's army camped at Valley Forge in December 1777, staying there for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men of the 10,000-strong force died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff. The British evacuated Philadelphia to New York in 1778 but Washington attacked them at Monmouth and drove them from the battlefield. Afterwards, the British continued to head towards New York. Washington moved his army outside of New York.

In the summer of 1779 at Washington's direction, General John Sullivan carried out a decisive scorched earth campaign that destroyed at least forty Iroquois villages throughout present-day central and upstate New York in retaliation for Iroquois and Tory attacks against American settlements earlier in the war. Washington, himself, had commercial interests in Ohio; his family had an investment in the Ohio Company, which was granted 500,000 acres of land in Ohio by King George III in 1747. Washington delivered the final blow to the British in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781, marked the end of most fighting.[30]

In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of Army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. By the Treaty of Paris (signed that September), Great Britain recognized the independence of the United States. Washington disbanded his army and, on November 2, gave an eloquent farewell address to his soldiers.[31]

On November 25, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession. At Fraunces Tavern on December 4, Washington formally bade his officers farewell and on December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief, emulating the Roman general Cincinnatus. He was an exemplar of the republican ideal of citizen leadership who rejected power. During this period, there was no position of President of the United States under the Articles of Confederation, the forerunner to the Constitution.

Washington's retirement to Mount Vernon was short-lived. He made an exploratory trip to the western frontier in 1784,[14] was persuaded to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, and was unanimously elected president of the Convention. He participated little in the debates (though he did vote for or against the various articles), but his high prestige maintained collegiality and kept the delegates at their labors. The delegates designed the presidency with Washington in mind, and allowed him to define the office once elected. After the Convention, his support convinced many, including the Virginia legislature, to vote for ratification; the new Constitution was ratified by all 13 states.

Presidency (1789–1797)

The Electoral College elected Washington unanimously in 1789, and again in the 1792 election; he remains the only president to have received 100 percent of the electoral votes.[32] At his inauguration, he John Adams was elected vice president. Washington took the oath of office as the first President under the Constitution for the United States of America on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City although, at first, he had not wanted the position.[33]

The 1st United States Congress voted to pay Washington a salary of $25,000 a year—a large sum in 1789. Washington, already wealthy, declined the salary, since he valued his image as a selfless public servant. At the urging of Congress, however, he ultimately accepted the payment, to avoid setting a precedent whereby the presidency would be perceived as limited only to independently wealthy individuals who could serve without any salary. Washington attended carefully to the pomp and ceremony of office, making sure that the titles and trappings were suitably republican and never emulated European royal courts. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President" to the more majestic names suggested.

Washington proved an able administrator. An excellent delegator and judge of talent and character, he held regular cabinet meetings to debate issues before making a final decision. In handling routine tasks, he was "systematic, orderly, energetic, solicitous of the opinion of others but decisive, intent upon general goals and the consistency of particular actions with them."[34]

Washington reluctantly served a second term as president. He refused to run for a third, establishing the customary policy of a maximum of two terms for a president, which later became law by the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution.[35]

Domestic issues

Washington was not a member of any political party and hoped that they would not be formed, fearing conflict and stagnation. His closest advisors formed two factions, setting the framework for the future First Party System. Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton had bold plans to establish the national credit and build a financially powerful nation, and formed the basis of the Federalist Party. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, founder of the Jeffersonian Republicans, strenuously opposed Hamilton's agenda, but Washington favored Hamilton over Jefferson.

The Residence Act of 1790, which Washington signed, authorized the President to select the specific location of the permanent seat of the government, which would be located along the Potomac River. The Act authorized the President to appoint three commissioners to survey and acquire property for this seat. Washington personally oversaw this effort throughout his term in office. In 1791, the commissioners named the permanent seat of government "The City of Washington in the Territory of Columbia" to honor Washington. In 1800, the Territory of Columbia became the District of Columbia when the federal government moved to the site according to the provisions of the Residence Act.[36][37]

In 1791, Congress imposed an excise on distilled spirits, which led to protests in frontier districts, especially Pennsylvania. By 1794, after Washington ordered the protesters to appear in U.S. district court, the protests turned into full-scale riots known as the Whiskey Rebellion. The federal army was too small to be used, so Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792 to summon the militias of Pennsylvania, Virginia, and several other states. The governors sent the troops and Washington took command, marching into the rebellious districts.[38] There was no fighting, but Washington's forceful action proved the new government could protect itself. It also was one of only two times that a sitting President would personally command the military in the field. These events marked the first time under the new constitution that the federal government used strong military force to exert authority over the states and citizens.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793[39] established the legal mechanism by which a slaveholder could recover his property, a right guaranteed by the Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article IV, Section 2). Passed overwhelmingly by Congress and signed into law by Washington, the 1793 Act made assisting an escaped slave a federal crime, overruled all state and local laws giving escaped slaves sanctuary, and allowed slave catchers into every U.S. state and territory. The law was not popular in the North, where state legislatures enacted personal liberty laws that protected freed blacks from being kidnapped and enslaved without being granted a trial or furnished with corroborative proof that the person was a slave.[40]

Foreign affairs

Morocco was the first country to recognize the United States in 1777, and Washington wrote to Mohammed ben Abdallah in appreciation of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship, signed in Marrakech in 1787.[41]

In 1793, the revolutionary government of France sent diplomat Edmond-Charles Genêt, called "Citizen Genêt," to America. Genêt issued letters of marque and reprisal to American ships so they could capture British merchant ships. He attempted to turn popular sentiment towards American involvement in the French war against Britain by creating a network of Democratic-Republican Societies in major cities. Washington rejected this interference in domestic affairs, demanded the French government recall Genêt, and denounced his societies. President Washington sent the French in their Haitian colony significant military weapons and $400,000 in money in an effort to put down a slave rebellion. [42]

Hamilton and Washington designed the Jay Treaty to normalize trade relations with Britain, remove them from western forts, and resolve financial debts left over from the Revolution. John Jay negotiated and signed the treaty on November 19, 1794. The Jeffersonians supported France and strongly attacked the treaty. Washington and Hamilton, however, mobilized public opinion and won ratification by the Senate by emphasizing Washington's support. The British agreed to depart from their forts around the Great Lakes, subsequently the U.S.-Canadian boundary had to be re-adjusted, numerous pre-Revolutionary debts were liquidated, and the British opened their West Indies colonies to American trade. Most importantly, the treaty delayed war with Britain and instead brought a decade of prosperous trade with Britain. The treaty angered the French and became a central issue in many political debates.

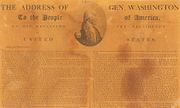

Farewell Address

Washington's Farewell Address (issued as a public letter in 1796) was one of the most influential statements of American political values.[43] Drafted primarily by Washington himself, with help from Hamilton, it gives advice on the necessity and importance of national union, the value of the Constitution and the rule of law, the evils of political parties, and the proper virtues of a republican people. While he declined suggested versions[44] that would have included statements that morality required a "divinely authoritative religion," he called morality "a necessary spring of popular government". He said, "Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle."[45]

Washington's public political address warned against foreign influence in domestic affairs and American meddling in European affairs. He warned against bitter partisanship in domestic politics and called for men to move beyond partisanship and serve the common good. He warned against 'permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world',[46] saying the United States must concentrate primarily on American interests. He counseled friendship and commerce with all nations, but warned against involvement in European wars and entering into long-term "entangling" alliances. The address quickly set American values regarding religion and foreign affairs.

Retirement and death (1797–1799)

After retiring from the presidency in March 1797, Washington returned to Mount Vernon with a profound sense of relief. He devoted much time to farming.

On July 4, 1798, Washington was commissioned by President John Adams to be lieutenant general and Commander-in-chief of the armies raised or to be raised for service in a prospective war with France. He served as the senior officer of the United States Army between July 13, 1798, and December 14, 1799. He participated in the planning for a Provisional Army to meet any emergency that might arise, but did not take the field.[14][47]

On December 12, 1799, Washington spent several hours inspecting his farms on horseback, in snow and later hail and freezing rain. He sat down to dine that evening without changing his wet clothes. The next morning, he awoke with a bad cold, fever, and a throat infection called quinsy that turned into acute laryngitis and pneumonia. Washington died on the evening of December 14, 1799, at his home aged 67, while attended by Dr. James Craik, one of his closest friends, Dr. Gustavus Richard Brown, Dr. Elisha C. Dick, and Tobias Lear V, Washington's personal secretary. Lear later recorded an account in his journal, writing that Washington's last words were "'Tis well." Modern doctors believe that Washington died largely because of his treatment, which included calomel and bloodletting, resulting in a combination of shock from the loss of five pints of blood, as well as asphyxia and dehydration.[48]

Throughout the world, men and women were saddened by Washington's death. Napoleon I ordered ten days of mourning throughout France; in the United States, thousands wore mourning clothes for months.[47] To protect their privacy, Martha Washington burned the correspondence between her husband and herself following his death. Only three letters between the couple have survived.

On December 18, 1799, a funeral was held at Mount Vernon, and Washington was interred in a tomb on the estate.[49]

Congress passed a joint resolution to construct a marble monument in the United States Capitol for his body, supported by Martha. In December 1800, the United States House passed an appropriations bill for $200,000 to build the mausoleum, which was to be a pyramid that had a base 100 feet (30 m) square. Southern opposition to the plan defeated the measure because they felt it was best to have his body remain at Mount Vernon.[50]

In 1831, for the centennial of his birth, a new tomb was constructed to receive his remains. That year, an attempt was made to steal the body of Washington, but proved to be unsuccessful.[51] Despite this, a joint Congressional committee in early 1832 debated the removal of Washington's body from Mount Vernon to a crypt in the Capitol, built by Charles Bullfinch in the 1820s. Yet again, Southern opposition proved very intense, antagonized by an ever-growing rift between North and South. Congressman Wiley Thompson of Georgia expressed the fear of Southerners when he said:

"Remove the remains of our venerated Washington from their association with the remains of his consort and his ancestors, from Mount Vernon and from his native State, and deposit them in this capitol, and then let a severance of the Union occur, and behold the remains of Washington on a shore foreign to his native soil."[52]

This ended any talk of the movement of his remains, and he was moved to the new tomb that was constructed there on October 7, 1837, presented by John Struthers of Philadelphia.[53] After the ceremony, the inner vault's door was closed and the key was thrown into the Potomac.[54]

Legacy

Representative Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee, a Revolutionary War comrade and father of the Civil War general Robert E. Lee, famously eulogized Washington as follows:

- First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen, he was second to none in humble and enduring scenes of private life. Pious, just, humane, temperate, and sincere; uniform, dignified, and commanding; his example was as edifying to all around him as were the effects of that example lasting...Correct throughout, vice shuddered in his presence and virtue always felt his fostering hand. The purity of his private character gave effulgence to his public virtues...Such was the man for whom our nation mourns.[10]

Lee's words set the standard by which Washington's overwhelming reputation was impressed upon the American memory. Washington set many precedents for the national government and the presidency in particular.

As early as 1778, Washington was lauded as the "Father of His Country".[57]

During the United States Bicentennial year, George Washington was posthumously appointed to the grade of General of the Armies of the United States by the congressional joint resolution Public Law 94-479 passed on January 19, 1976, with an effective appointment date of July 4, 1976.[14] This restored Washington's position as the highest-ranking military officer in U.S. history.

Monuments and memorials

Today, Washington's face and image are often used as national symbols of the United States, along with the icons such as the flag and great seal. He appears on contemporary currency, including the one-dollar bill and the quarter coin, and on U.S. postage stamps. Along with appearing on the first postage stamps issued by the U.S. Post Office in 1847,[55] Washington has been depicted on U.S. postage stamps more than all other notable Americans combined, including Abraham Lincoln and Benjamin Franklin.[55] Washington, together with Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln, is depicted in stone at the Mount Rushmore Memorial. The Washington Monument, one of the most well known American landmarks, was built in his honor. The George Washington Masonic National Memorial in Alexandria, Virginia, was constructed between 1922–32 with voluntary contributions from all 52 local governing bodies of the Freemasons in the United States.[58][59]

Many things have been named in honor of Washington. Washington's name became that of the nation's capital, Washington, D.C., one of two capitals across the globe to be named after an American president (the other is Monrovia, Liberia). The state of Washington is the only state to be named after an American (Maryland, Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia are all named in honor of British monarchs, and Pennsylvania and Delaware after British subjects). George Washington University and Washington University in St. Louis were named for him, as was Washington and Lee University (once Washington Academy), which was renamed due to Washington’s large endowment in 1796. Countless American cities and towns feature a Washington Street among their thoroughfares.

The Confederate Seal prominently featured George Washington on horseback, in the same position as a statue of him in Richmond, Virginia.

London hosts a standing statue of Washington, one of 22 bronze identical replicas. Based on Jean Antoine Houdon's original marble statue in the Rotunda of the State Capitol in Richmond, Virginia, the duplicate was given to the British in 1921 by the Commonwealth of Virginia. It stands in front of the National Gallery at Trafalgar Square.[60]

Personal life

Along with Martha's biological family noted above, George Washington had a close relationship with his nephew and heir Bushrod Washington, son of George's younger brother John Augustine Washington. Bushrod became an Associate Justice on the US Supreme Court after George's death.

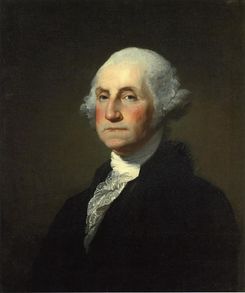

As a young man, Washington had red hair.[61][62] A popular myth is that he wore a wig, as was the fashion among some at the time. Washington did not wear a wig; instead, he powdered his hair,[63] as represented in several portraits, including the well known unfinished Gilbert Stuart depiction.[64]

Washington suffered from problems with his teeth throughout his life. He lost his first adult tooth when he was twenty-two and had only one left by the time he became President.[65] John Adams claims he lost them because he used them to crack Brazil nuts but modern historians suggest the mercury oxide, which he was given to treat illnesses such as smallpox and malaria, probably contributed to the loss. He had several sets of false teeth made, four of them by a dentist named John Greenwood.[65] Contrary to popular belief, none of the sets were made from wood. The set made when he became President was carved from hippopotamus and elephant ivory, held together with gold springs.[66] The hippo ivory was used for the plate, into which real human teeth and bits of horses' and donkeys' teeth were inserted. Dental problems left Washington in constant pain, for which he took laudanum.[67] This distress may be apparent in many of the portraits painted while he was still in office, including the one still used on the $1 bill.

One of the most enduring myths about George Washington involves his chopping down his father's cherry tree and, when asked about it, using the famous line "I cannot tell a lie, I did it with my little hatchet." There is no evidence that this ever occurred.[68] It, along with the story of Washington skipping a silver dollar across the Potomac River, was part of a book of mythic stories written by Mason Weems that made Washington a legendary figure beyond his wartime and presidential achievements.

Slavery

The slave trade continued throughout George Washington’s life. On the death of his father in 1743, the 11-year-old inherited 10 slaves. At the time of his marriage to Martha Custis in 1759, he personally owned at least 36 (and the widow's third of her first husband's estate brought at least 85 "dower slaves" to Mount Vernon). Using his wife's great wealth he bought land, tripling the size of the plantation, and additional slaves to farm it. By 1774, he paid taxes on 135 slaves (this does not include the "dowers"). The last record of a slave purchase by him was in 1772, although he later received some slaves in repayment of debts.[69] Washington also used white indentured servants.[70][71]

Before the American Revolution, Washington expressed no moral reservations about slavery, but in 1786, Washington wrote to Robert Morris, saying, "There is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of slavery."[72] In 1778, he wrote to his manager at Mount Vernon that he wished "to get quit of negroes". Maintaining a large, and increasingly elderly, slave population at Mount Vernon was not economically profitable. Washington could not legally sell the "dower slaves," however, and because these slaves had long intermarried with his own slaves, he could not sell his slaves without breaking up families.[73]

As president, Washington brought seven slaves to New York City in 1789 to work in the first presidential household– Oney Judge, Moll, Giles, Paris, Austin, Christopher Sheels, and William Lee. Following the transfer of the national capital to Philadelphia in 1790, he brought nine slaves to work in the President's House– Oney Judge, Moll, Giles, Paris, Austin, Christopher Sheels, Hercules, Richmond, and Joe (Richardson).[74] Oney Judge and Hercules escaped to freedom from Philadelphia, and there were foiled escape attempts from Mount Vernon by Richmond and Christopher Sheels.

Pennsylvania had begun an abolition of slavery in 1780, and prohibited nonresidents from holding slaves in the state longer than six months. If held beyond that period, the state's Gradual Abolition Act[75] gave those slaves the power to free themselves. Washington argued (privately) that his presence in Pennsylvania was solely a consequence of Philadelphia's being the temporary seat of the federal government, and that the state law should not apply to him. On the advice of his attorney general, Edmund Randolph, he systematically rotated the President's House slaves in and out of the state to prevent their establishing a six-month continuous residency. This rotation was itself a violation of the Pennsylvania law, but the President's actions were not challenged.

Washington was the only prominent, slaveholding Founding Father who emancipated his slaves. His actions were influenced by his close relationship with Marquis de La Fayette. He did not free his slaves in his lifetime, however, but included a provision in his will to free his slaves upon the death of his wife. At the time of his death, there were 317 slaves at Mount Vernon– 123 owned by Washington, 154 "dower slaves," and 40 rented from a neighbor.[76]

Martha Washington bequeathed the one slave she owned outright– Elisha– to her grandson George Washington Parke Custis. Following her death in 1802, her grandchildren inherited the dower slaves.

It has been argued that Washington did not speak out publicly against slavery, because he did not wish to create a split in the new republic, with an issue that was sensitive and divisive.[77] Even if Washington had opposed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, his veto probably would have been overridden. (The Senate vote was not recorded, but the House passed it overwhelmingly, 47 to 8.)[78]

On March 4, 1850, the possibility of Southern Secession over the issue of slavery, eventually deferred by the Compromise of 1850, arose. The prominent Southern leader John C. Calhoun invoked Washington's memory in support of the Southern cause, saying, "The illustrious Southerner whose mortal remains repose on the western bank of the Potomac was one of us — a slave-holder and a planter" [79]

Religious beliefs

Washington was baptized into the Church of England when he was less than two months old.[80][81] In 1765, when the Church of England was still the state religion,[82] he served on the vestry (lay council) for his local church. Throughout his life, he spoke of the value of righteousness, and of seeking and offering thanks for the "blessings of Heaven."

From his own writings, Washington practically speaking was a Deist who had a profound belief and faith in "Providence" or a higher "Devine Will" that controlled human events and as in Calvinism the course of history followed an orderly pattern rather than mere chance. In 1789 he claimed that the "Author of the Universe" actively interposed in favor of the American Revolution. However, according to one historian, Paul F. Boller Jr., Washington never made attempts to personalize his own religious views or express any appeal to the aesthetic side of biblical passages. Boller states that Washington's "allusions to religion are almost totally lacking in depths of feeling."[83]

In a letter to George Mason in 1785, Washington wrote that he was not among those alarmed by a bill "making people pay towards the support of that [religion] which they profess," but felt that it was "impolitic" to pass such a measure, and wished it had never been proposed, believing that it would disturb public tranquility.[84]

His adopted daughter, Nelly Custis Lewis, stated: "I have heard her [Nelly's mother, Eleanor Calvert Custis, who resided in Mount Vernon for two years] say that General Washington always received the sacrament with my grandmother [Martha Washington] before the revolution."[85] Washington frequently accompanied his wife to Christian church services; however, there is no record of his ever taking communion, and he would regularly leave services before communion—with the other non-communicants (as was the custom of the day), until, after being admonished by a rector, he ceased attending at all on communion Sundays.[86][87] Before communion, believers are admonished to take stock of their spiritual lives and not to participate in the ceremony unless he finds himself in the will of God.[85][88] Historians and biographers continue to debate the degree to which he can be counted as a Christian, and the degree to which he was a deist.

He was an early supporter of religious toleration and freedom of religion. In 1775, he ordered that his troops not show anti-Catholic sentiments by burning the pope in effigy on Guy Fawkes Night. When hiring workmen for Mount Vernon, he wrote to his agent, "If they be good workmen, they may be from Asia, Africa, or Europe; they may be Mohammedans, Jews, or Christians of any sect, or they may be Atheists."[88][89] In 1790, he wrote a response to a letter from the Touro Synagogue, in which he said that as long as people remain good citizens, they do not have to fear persecution for having differing beliefs or faiths. This was a relief to the Jewish community of the United States, since the Jews had been either expelled or discriminated against in many European countries.

- ...the Government of the United States ... gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance. ... May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.

The United States Bill of Rights was in the process of being ratified at the time.

Freemasonry

On November 4, 1752, George Washington was initiated into Freemasonry in Fredericksburg lodge.[90] On April 29, 1788, he was appointed Worshipful Master of Alexandria Lodge 22,[91] and held that office when he was elected President of the United States. At his inauguration, the Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of New York administered his oath of office. On September 18, 1793, he laid the cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol wearing full Masonic Grand Master regalia.

See also

- 1932 Washington Bicentennial

- George Washington bibliography

- List of federal judges appointed by George Washington

- Military career of George Washington

- Town Destroyer, a nickname given to Washington by the Iroquois

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Engber, Daniel (2006).What's Benjamin Franklin's Birthday?. (Both Franklin's and Washington's confusing birth dates are clearly explained.) Retrieved on June 17, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 The birth and death of George Washington are given using the Gregorian calendar. However, he was born when Britain and her colonies still used the Julian calendar, so contemporary records record his birth as February 11, 1731. The provisions of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, implemented in 1752, altered the official British dating method to the Gregorian calendar with the start of the year on January 1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Image of page from family Bible". Papers of George Washington. http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/project/faq/bible.html. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ↑ Under the Articles of Confederation Congress called its presiding officer "President of the United States in Congress Assembled". He had no executive powers, but the similarity of titles has confused people into thinking there were other presidents before Washington. Merrill Jensen, The Articles of Confederation (1959), 178–9

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "George Washington". Library of Congress. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/cgi-bin/page.cgi/aa/wash. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Rediscovering George Washington". Public Broadcasting Service. http://www.pbs.org/georgewashington/father/index.html. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ↑ Richard Brookhiser "George Washington, Founding CEO," American Heritage, Spring/Summer 2008.

- ↑ Daniel C. Gedacht. George Washington: Leader of a New Nation. The Rosen Publishing Group, 2004. p. 99. ISBN 0823966224. http://books.google.com/books?id=-9TNKUwsPYIC&pg=PT73&dq=George+Washington+king+george+III++%22the+greatest+character+of+the+age%22&hl=en&ei=t6V1TIjdIo-64QbX6NiGBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CC4Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=George%20Washington%20king%20george%20III%20%20%22the%20greatest%20character%20of%20the%20age%22&f=false. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Loubat, J. F. and Jacquemart, Jules, Illustrator, The Medallic History of the United States of America 1776–1876". Gutenberg.org. 2007-06-20. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/21880. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Henry Lee's eulogy to George Washington, December 26, 1799. Safire, William (2004). Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-393-05931-6.

- ↑ Dorothy Twohig, "The Making of George Washington", in Warren R. Hofstra, ed., George Washington and the Virginia Backcountry (Madison, 1998).

- ↑ Mastromarino, Mark. Biography of George Washington. The Papers of George Washington. Alderman Library. University of Virginia. URL retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ↑ John Fitzpatrick, in Dictionary of American Biography, Volume 10 (1936)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 Bell, William Gardner (1983). Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff: 1775–2005; Portraits & Biographical Sketches of the United States Army's Senior Officer. Center of Military History – United States Army. pp. 52 & 66. CMH Pub 70–14. ISBN 0160723760. http://www.history.army.mil/books/CG&CSA/CG-TOC.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ↑ Fred Anderson, Crucible of War (Vintage Books, 2001), p. 6.

- ↑ "Seven Years' War - The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0007300. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ↑ Edward G. Lengel. [http://books.google.com/books?id=B4prSx7i8wMC&dq=General+George+Washington:+A+Military+Life&hl=en&ei=aJx1TK7sOOSd4Ab8nvCyBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA General George Washington: A Military Life]. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2007. p. 48. http://books.google.com/books?id=B4prSx7i8wMC&dq=General+George+Washington:+A+Military+Life&hl=en&ei=aJx1TK7sOOSd4Ab8nvCyBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAA. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ↑ On British attitudes see John Shy, Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (1990) p. 39; Douglas Edward Leach. Roots of Conflict: British Armed Forces and Colonial Americans, 1677–1763 (1986) p. 106; and John Ferling. Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution (2002) p. 65

- ↑ Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. (2004) ISBN 1-4000-4031-0.

- ↑ For negative treatments of Washington's excessive ambition and military blunders, see Bernhard Knollenberg, George Washington: The Virginia Period, 1732–1775 (1964) and Thomas A. Lewis, For King and Country: The Maturing of George Washington, 1748–1760 (1992).

- ↑ Garance Franke-Ruta, "George Washington's Bioterrorism Strategy" http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2001/0112.franke-ruta.html

- ↑ "Acreage, slaves, and social standing", Joseph Ellis, His Excellency, George Washington, pp. 41–42, 48.

- ↑ Fox hunting: Ellis p. 44. Mount Vernon economy: John Ferling, The First of Men, pp. 66–67; Ellis pp. 50–53; Bruce A. Ragsdale, "George Washington, the British Tobacco Trade, and Economic Opportunity in Pre-Revolutionary Virginia", in Don Higginbotham, ed., George Washington Reconsidered, pp. 67–93.

- ↑ Washington, quoted in Ferling, p. 99.

- ↑ Orlando W. Stephenson, "The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776", American Historical Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (January 1925), pp. 271–281 in JSTOR

- ↑ Bickham, Troy O. "Sympathizing with Sedition? George Washington, the British Press, and British Attitudes During the American War of Independence", William and Mary Quarterly 2002 59(1): 101–122. ISSN 0043-5597 Fulltext online in History Cooperative

- ↑ McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743226714.

- ↑ George Washington Biography, American-Presidents.com. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ↑ Fleming, T: "Washington's Secret War: the Hidden History of Valley Forge", Smithsonian Books, 2005

- ↑ Mann (2005), George Washington's War on Native America, page 38

- ↑ George Washington Papers 1741–1799: Series 3b Varick Transcripts, American Memory, Library of Congress, Accessed May 22, 2006.

- ↑ Under the system in place at the time, each elector cast two votes, with the winner becoming president and the runner-up vice president. All electors in the elections of 1789 and 1792 cast one of their votes for Washington; thus it may be said that he was elected president unanimously.

- ↑ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). "Washington's First Administration: 1789–1793". The Oxford History of the American People, Vol. 2. Meridian. ISBN 0451622545.

- ↑ Leonard D. White, The Federalists: A Study in Administrative History (1948)

- ↑ After Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented four terms, the two-term limit was formally integrated into the Federal Constitution by the twenty-second Amendment.

- ↑ Crew, Harvey W., Webb, William Bensing, Wooldridge, John, Centennial History of the City of Washington, D.C., United Brethren Publishing House, Dayton, Ohio, 1892, Chapter IV. "Permanent Capital Site Selected", p. 87 in Google Books. Accessed May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Text of Residence Act in ""American Memory" in official website of the U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ↑ Hoover, Michael. "The Whiskey Rebellion". United States Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. http://www.ttb.gov/public_info/whisky_rebellion.shtml. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ↑ "The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793". Ushistory.org. 1995-07-04. http://www.ushistory.org/presidentshouse/history/slaveact1793.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ "Fugitive Slave Act of 1793". http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h480.html. Retrieved 08-26-2010. Cambel (1970), The Slave Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Capitalizing on the Morocco-US Free Trade Agreement: a road map for success by Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Claire Brunel p.1

- ↑ Hunt (1988), Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Matthew Spalding, The Command of its own Fortunes: Reconsidering Washington's Farewell Address", in William D. Pederson, Mark J. Rozell, Ethan M. Fishman, eds. George Washington (2001) ch 2; Virginia Arbery, "Washington's Farewell Address and the Form of the American Regime" in Gary L. Gregg II and Matthew Spalding, eds. George Washington and the American Political Tradition. 1999 pp. 199–216.

- ↑ "Library of Congress – see Farewell Address section". Loc.gov. 2003-10-27. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/rel06.html. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ "Religion and the Federal Government". Religion and the Founding of the American Republic. Library of Congress Exhibition. Retrieved on May 17, 2007.

- ↑ "Washington's Farewell Address, 1796"

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 The World Book Encyclopedia. W*X*Y*Z (1969 ed.). Field Enterprises Educational Corporation. 1969 [1917]. p. 84a. LOC 69-10030.

- ↑ Vadakan, M.D., Vibul V. (Winter/Spring 2005). "A Physician Looks At The Death of Washington". Early America Review. Archiving Early America. http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2005_winter_spring/washingtons_death.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ↑ "The Funeral". The Papers of George Washington. University of Virginia. http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/project/exhibit/mourning/funeral.html.

- ↑ Boorstin, Daniel (1965). The Americans: The National Experience. Vintage Books. pp. 349–350. ISBN 394703588.

- ↑ Johnston, Elizabeth Bryant (1889). Visitors' Guide to Mount Vernon. Gibson Brothers, Printers. pp. 14–15. http://books.google.com/?id=7p5BAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA14.

- ↑ Boorstin, p. 350.

- ↑ Washington, George; Jefferson, Thomas; Peters, Richard (1847). Knight, Franklin. ed. Letters on Agriculture. Washington: Franklin Knight. pp. 177–180. http://books.google.com/?id=N58TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA177-IA1. Retrieved February 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Mount Vernon Visited; The Home of Washington As It Exists Today". The New York Times: p. 2. March 12, 1881. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9C05E3DE133EE433A25751C1A9659C94609FD7CF. "The body was placed in this sarcophagus on October 7, 1837, when the door of the inner vault was closed and the key thrown in the Potomac."

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Scotts Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps

- ↑ "George and Martha Washington: Portraits from the Presidential Years". www.npg.si.edu. http://www.npg.si.edu/exh/gw/gwsharp.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ↑ He has gained fame around the world as a quintessential example of a benevolent national founder. Gordon Wood concludes that the greatest act in his life was his resignation as commander of the armies—an act that stunned aristocratic Europe. Gordon Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1992), pp 105–6; Edmund Morgan, The Genius of George Washington (1980), pp 12–13; Sarah J. Purcell, Sealed With Blood: War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary America (2002) p. 97; Don Higginbotham, George Washington (2004); Ellis, 2004. The earliest known image in which Washington is identified as such is on the cover of the circa 1778 Pennsylvania German almanac (Lancaster: Gedruckt bey Francis Bailey).

- ↑ Charles Callahan. Washington: The Man and the Mason. Kessinger Publishing, 1998. pp. 329–342. ISBN 0766102459. http://books.google.com/books?id=IyWnb10FTyYC&pg=PA332&dq=The+George+Washington+Masonic+Memorial&hl=en&ei=LCl1TOTHBs2TjAe64ZChBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDcQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=The%20George%20Washington%20Masonic%20Memorial&f=false. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ↑ John Weber. An Illustrated Guide to the Lost Symbol. Simon and Schuster, 2009. p. 137. ISBN 1416523669. http://books.google.com/books?id=l2h7IWKhCrIC&pg=PA137&dq=The+George+Washington+Masonic+Memorial&hl=en&ei=LCl1TOTHBs2TjAe64ZChBg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=The%20George%20Washington%20Masonic%20Memorial&f=false. Retrieved 2010-08-25.

- ↑ Statue of George Washington, http://encyclopedia.gwu.edu/gwencyclopedia/index.php?title=Houdon_Statue_of_George_Washington, retrieved 24 August 2010

- ↑ Homans, Charles (2004-10-06). "Taking a New Look at George Washington". The Papers of George Washington: Washington in the News. Alderman Library, University of Virginia. http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/articles/news/chicago.html. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ↑ Ross, John F (October 2005). Unmasking George Washington. Smithsonian Magazine.

- ↑ "George Washington's Mount Vernon: Answers". http://www.mountvernon.org/visit/plan/index.cfm/pid/446/. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- ↑ Gilbert Stuart. "Smithsonian National Picture Gallery: George Washington (the Athenaeum portrait)". http://www.npg.si.edu/cexh/stuart/athen1.htm. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Lloyd, John; Mitchinson, John (2007). The Book of General Ignorance. Harmony. p. 97. ISBN 9780307394910. http://books.google.com/?id=1Mjd2GCRPmAC&pg=PA97.

- ↑ Barbara Glover. "George Washington - A Dental Victim". http://www.americanrevolution.org/dental.html. Retrieved 2006-06-30.

- ↑ "George Washington Portrait: A National Treasure". Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. http://www.georgewashington.si.edu/portrait/face.html. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ↑ Nicholas F. Gier, University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho (1980 and 2005). "Religious Liberalism and the Founding Fathers". http://www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/305/foundfathers.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ↑ Fritz Hirschfeld, George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal, University of Missouri, 1997, pp. 11–12

- ↑ "The forgotten history of Britain's white slaves". Telegraph.co.uk. May 3, 2007.

- ↑ "George Washington: Farmer", by Paul Leland Haworth.

- ↑ Letter of April 12, 1786, in W. B. Allen, ed., George Washington: A Collection (Indianapolis: Library Classics, 1989), 319.

- ↑ Slave raffle linked to Washington's reassessment of slavery: Wiencek, pp. 135–36, 178–88. Washington's decision to stop selling slaves: Hirschfeld, p. 16. Influence of war and Wheatley: Wiencek, ch 6. Dilemma of selling slaves: Wiencek, p. 230; Ellis, pp. 164–7; Hirschfeld, pp. 27–29.

- ↑ "Biographical sketches of the 9". Ushistory.org. 1995-07-04. http://www.ushistory.org/presidentshouse/slaves/index.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ "Pennsylvania's Gradual Abolition Law (1780)". Ushistory.org. 1995-07-04. http://www.ushistory.org/presidentshouse/history/gradual.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ "1799 Mount Vernon Slave Census". Gwpapers.virginia.edu. http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/documents/will/slavelist.html. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ Twohig, "That Species of Property", pp. 127–28.

- ↑ "Slavery by the Numbers". Ushistory.org. 1995-07-04. http://www.ushistory.org/presidentshouse/slaves/numbers.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

- ↑ Speech published in "The Penguin Book of Historical Speeches", Ed. Brian MacArthur, London, 1995, P. 255

- ↑ "George Washington Birthplace - National Monument - Family Bible entry". National Park Service Online Books. http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/hh/26/hh26f.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ↑ "The Papers of George Washington - Image of Bible Record for Washington Family". University of Virginia. http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/project/faq/bible.html. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ↑ Colonial Williamsburg website has several articles on religion in colonial Virginia

- ↑ Boller (1963), George Washington & Religion, pages 92-109

- ↑ "George Washington to George Mason, October 3, 1785, LS". Library of Congress: American Memory. http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mgw/mgw2/012/2440242.jpg. Retrieved 2006-09-05.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "Proof that Washington was a Christian?". ushistorg.org. http://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/youasked/060.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-17. includes 1833 letter from Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis to Jared Sparks

- ↑ Sprague, Rev. Wm. B. (1859). Annals of the American Pulpit. Vol. v. Robert Carter & Brothers. pp. 394. http://books.google.com/?id=_xISAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA394&dq=sprague+annals+abercrombie+washington.

- ↑ Neill, Rev. E.D. (1885-01-02). "article reprinted from Episcopal Recorder" (PDF). NY Times. pp. 3. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9404E1DA1138E033A25751C0A9679C94649FD7CF&oref=slogin.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Steiner, Franklin. "The Religious Beliefs of Our Presidents". Internet Infidels. http://www.infidels.org/library/historical/franklin_steiner/presidents.html#1.

- ↑ Boller, Paul F (1963). George Washington & Religion. p. 118. ISBN 0870740210. letter to Tench Tilghman asking him to secure a carpenter and a bricklayer for his Mount Vernon estate, March 24, 1784

- ↑ "Washington as a Freemason". Phoenixmasonry.org. http://www.phoenixmasonry.org/washington_as_a_freemason.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ↑ http://www.francmasoncoleccion.es/2-GEORGE-WASHINGTON-MASON-MASONERIA/george-washington-as-mason-masones-famosos.php

- Bibliography

- Buchanan, John. The Road to Valley Forge: How Washington Built the Army That Won the Revolution (2004). 368 pp.

- Burns, James MacGregor and Dunn, Susan. George Washington. Times, 2004. 185 pp. explore leadership style

- Cunliffe, Marcus. George Washington: Man and Monument (1958), explores both the biography and the myth

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. George! A Guide to All Things Washington. Buena Vista and Charlottesville, VA: Mariner Publishing. 2005. ISBN 0-9768238-0-2. Grizzard is a leading scholar of Washington.

- Hirschfeld, Fritz. George Washington and Slavery: A Documentary Portrayal. University of Missouri Press, 1997.

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. (2004) ISBN 1-4000-4031-0. Acclaimed interpretation of Washington's career.

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. (1994) the leading scholarly history of the 1790s.

- Ferling, John E. The First of Men: A Life of George Washington (1989). Biography from a leading scholar.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. (2004), prize-winning military history focused on 1775–1776.

- Flexner, James Thomas. Washington: The Indispensable Man. (1974). ISBN 0-316-28616-8 (1994 reissue). Single-volume condensation of Flexner's popular four-volume biography.

- Freeman, Douglas S. George Washington: A Biography. 7 volumes, 1948–1957. The standard scholarly biography, winner of the Pulitzer Prize. A single-volume abridgement by Richard Harwell appeared in 1968

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. George Washington: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO, 2002. 436 pp. Comprehensive encyclopedia by leading scholar

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. The Ways of Providence: Religion and George Washington. Buena Vista and Charlottesville, VA: Mariner Publishing. 2005. ISBN 0-9768238-1-0.

- Higginbotham, Don, ed. George Washington Reconsidered. University Press of Virginia, (2001). 336 pp of essays by scholars

- Higginbotham, Don. George Washington: Uniting a Nation. Rowman & Littlefield, (2002). 175 pp.

- Hofstra, Warren R., ed. George Washington and the Virginia Backcountry. Madison House, 1998. Essays on Washington's formative years.

- Lengel, Edward G. General George Washington: A Military Life. New York: Random House, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-6081-8.

- Lodge, Henry Cabot. George Washington, 2 vols. (1889), vol 1 at Gutenberg; vol 2 at Gutenberg

- McDonald, Forrest. The Presidency of George Washington. 1988. Intellectual history showing Washington as exemplar of republicanism.

- Smith, Richard Norton Patriarch: George Washington and the New American Nation Focuses on last 10 years of Washington's life.

- Spalding, Matthew. "George Washington's Farewell Address", The Wilson Quarterly v20#4 (Autumn 1996) pp: 65+.

- Stritof, Sheri and Bob. "George and Martha Washington"

- Wiencek, Henry. An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America. (2003).

External links

- Works by George Washington at Project Gutenberg

- George Washington Resources from the University of Virginia

- George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate & Gardens

- George Washington from the Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia

- Washington's Commission as Commander in Chief from the Library of Congress

- George Washington Birthplace National Monument from the National Park Service

- Painting of John Gano Baptizing George Washington

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||